Why Avoidant Dynamics Hit Harder After 40, 50, 60+

If you handled breakups and emotional uncertainty relatively well in your 20s and 30s, yet now find yourself in your 40s, 50s or 60s feeling completely destabilised by an avoidant partner… nothing is wrong with you.

Later-life attachment reactions are not signs of regression, weakness or immaturity.

They are the predictable outcome of how attachment, the nervous system, identity and relational learning evolve across decades.

When an avoidant dynamic appears later in life, it doesn’t just activate the present situation. It activates your entire history of attachment conditioning.

This article explains the psychological, neurological, and relational reasons why avoidant behaviour hits harder later in life - and what that means for healing and reconnection.

1. Attachment patterns become more “crystallised” with age - but not fixed

Attachment style isn’t a personality trait. It’s an adaptation to early and ongoing relational environments.

Longitudinal research shows two important truths:

- Attachment is moderately stable

- Attachment can and does change with life events

A 6-year study by Waters, Weinfield & Hamilton (2000) found that major stressors - divorce, illness, loss - caused significant shifts in attachment security. Another major review by Mikulincer & Shaver (2016) confirms that adulthood attachment remains plastic, not permanent.

What does this mean for you?

Your attachment system at 50 or 60 is not a blank slate. It is:

- Layered

- Conditioned by decades of relationships

- Influenced by long-term coping strategies

So avoidant behaviour now doesn’t hit “fresh territory.” It hits well-worn neural pathways.

2. Emotional goals shift later in life: connection becomes a higher priority

Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (Carstensen, 1992) shows that as people age, they:

- Prioritise emotionally meaningful relationships

- Seek less novelty and more emotional safety

- Become more selective with time and attention

- React more strongly to relational threats because stability matters more

- Experience deeper longing for secure connection

This means:

In your 20s, distance in a relationship feels like a setback. In your 50s or 60s, it feels like a threat to the life you want to build, protect or repair.

We are not less emotional with age. We are more emotionally intentional, and therefore more sensitive to relational instability.

3. Older adults feel emotional pain differently - often more intensely

There’s a common myth that people “toughen up” emotionally with age. But research says the opposite in certain contexts.

Studies on emotional reactivity show:

- Older adults can have stronger physiological responses to emotional threat (Shiota et al., 2011)

- They recover faster from everyday stress - but not from attachment-relevant threat

- Loss, abandonment and relational uncertainty hit harder because they conflict with core goals (Charles & Carstensen, 2010)

So if your avoidant partner pulls back, your body may respond with:

- Crushing panic

- Loss of appetite

- Insomnia

- Identity confusion

- Emotional flashbacks

- Rumination loops

This is not a sign of “losing control.” It is your nervous system trying to reconcile a major relational threat at a stage of life where meaning and stability matter most.

4. Late-life breakups cut deeper into identity

The rise of “grey divorce” (divorce after age 50) has been widely researched.

Findings:

- People experience identity disruption, not just relational loss (Brown & Lin, 2012).

- There is increased loneliness, emotional shock, and narrative collapse.

- Many report feeling “I don’t know who I am off this relationship.”

- The emotional consequences can last longer than earlier-life breakups.

So when an avoidant partner distances themselves, it interacts with:

- The story you’ve built about yourself

- The life you thought you were re-entering

- Your hopes for connection post-divorce

- Your fears about starting over

- A lifetime of emotional patterning

This makes avoidant behaviour feel like a threat to:

- Your emotional stability

- Your sense of self

- Your vision of the future

It’s not “just a breakup.” It’s a collision with meaning, identity, and time.

5. Avoidant partners use deactivating strategies that feel destabilising when you’re older

Avoidantly attached adults cope with closeness by suppressing attachment needs and distancing themselves (Fraley & Shaver, 2000).

This leads to:

- Shutdown

- Emotional minimising

- Dismissive responses

- Disappearing during conflict

- Focusing on work or distractions

- Avoiding emotional conversations

- Ending relationships abruptly when overwhelmed

When you’ve spent years - maybe decades - carrying emotional responsibility for relationships, these behaviours feel like:

- Personal rejection

- Threat

- Confusion

- Betrayal

- Instability

- Abandonment

And because you’ve lived long enough to accumulate relational wounds, this withdrawal touches every one of them at once.

That’s why it feels unbearable.

6. The nervous system becomes more sensitive to relational threat later in life

Attachment-related distress activates:

- The amygdala (threat detection)

- The insula (emotional awareness)

- The anterior cingulate cortex (pain processing)

Older adults often show:

- Greater amygdala responsiveness to unpredictable negative stimuli

- Lower tolerance for prolonged uncertainty

- Higher cortisol activation in chronic relational stress

- Stronger cognitive-emotional linking (memories + present threat)

This means your system may interpret avoidant withdrawal as:

“I’m not safe.” “I’m about to lose something that matters.” “This will not resolve unless I fix it.”

And because you’ve survived decades of relational stress, you might have hypertrained coping strategies:

- Fixing

- Explaining

- Over-functioning

- Absorbing blame

- Chasing

Those strategies intensify the avoidant’s deactivation - and the cycle spirals.

7. Why this dynamic often feels WORSE for people who are smart, successful and emotionally literate

Because you’ve built:

- Strong career identity

- Strong social intelligence

- A long history of solving problems

- Competence in other areas of life

- Emotional awareness

So when an avoidant partner sends your system into collapse, it violates your self-image:

“I’m good at everything else - why is this breaking me?”

From a scientific standpoint, that question has an answer:

You’re not failing. You’re being triggered in the deepest, oldest part of the attachment system, which is stronger than logic.

8. The good news: later-life attachment change is absolutely possible

Attachment is plastic - even late in adulthood. Therapies like EFT consistently show reductions in avoidance and anxiety when partners experience responsive engagement (Johnson et al., 2013).

Older adults also:

- Use more reappraisal (cognitive reframing)

- Have higher emotional wisdom

- Are more motivated to resolve conflict

- Recover faster once clarity is achieved

- Are often highly motivated to break patterns

This is why people in their 50s–70s often make faster progress toward secure functioning than younger clients.

Your system is not broken.

It’s ready for an update.

9. What this means for you

If avoidant behaviour is destabilising you more now than ever:

- You’re not weak

- You’re not “too old”

- You’re not emotionally behind

- You’re not overreacting

You’re being asked to confront a lifetime of relational programming - at a stage when connection matters deeply.

And that is solvable.

If you'd like to see how this plays out in real life, watch:

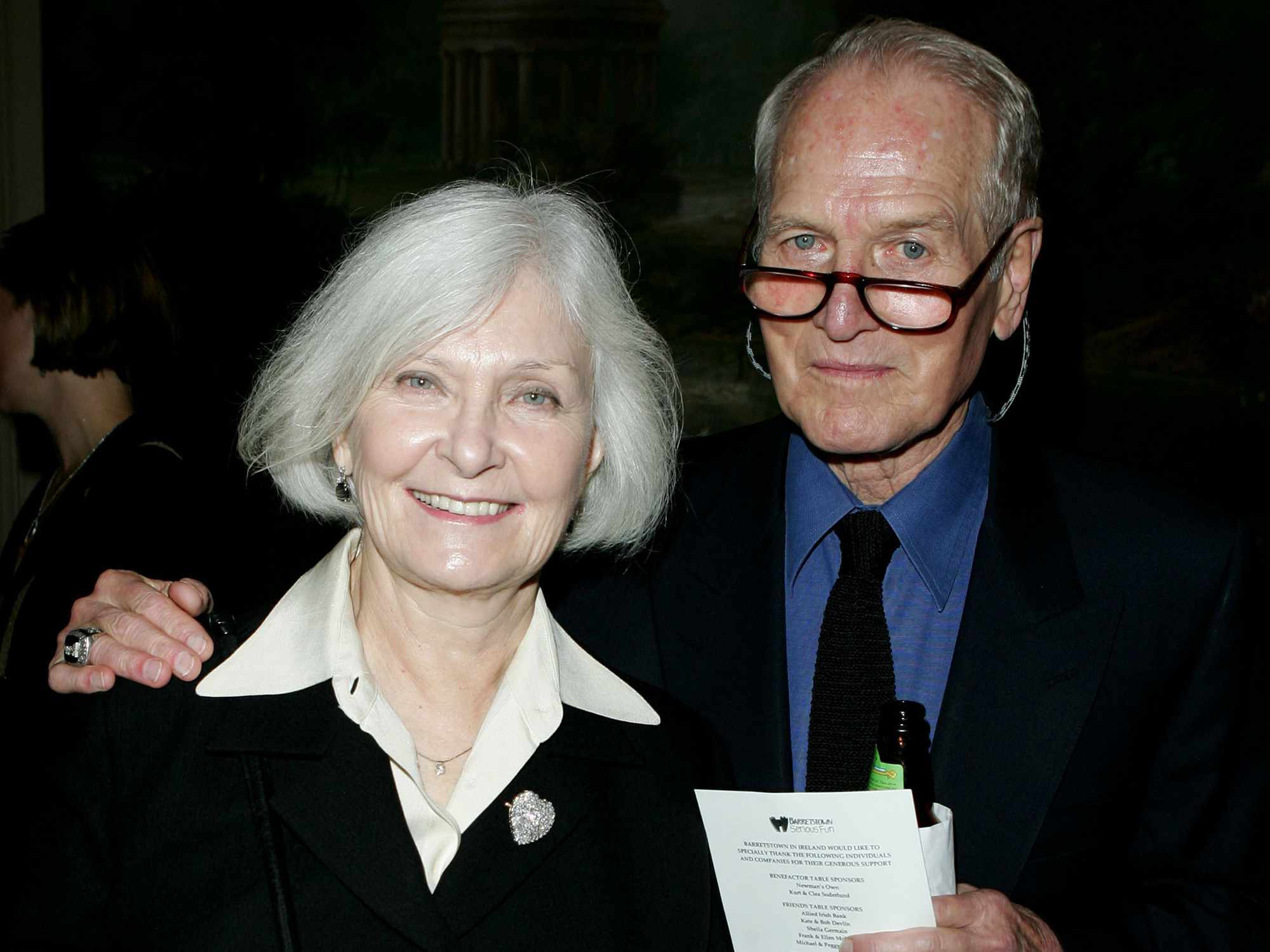

Interview of Sue who got back with her ex at 62

Interview of Laura who developped a secure attachment style in her 60s

References

- Brown, S. L., & Lin, I.-F. (2012). The Gray Divorce Revolution. Journals of Gerontology Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs009

- Carstensen, L. L. (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for the socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 331–338.

- Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and Emotional Aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409.

- Fraley, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 132–154.

- Johnson, S. M., et al. (2013). Embracing the attachment bond: EEG and fMRI support. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy.

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. Guilford Press.

- Shiota, M. N., Cate, R. A., & Levenson, R. W. (2011). Negative Emotional Responses in Older vs. Younger Adults. Emotion, 11(4), 1020–1030.